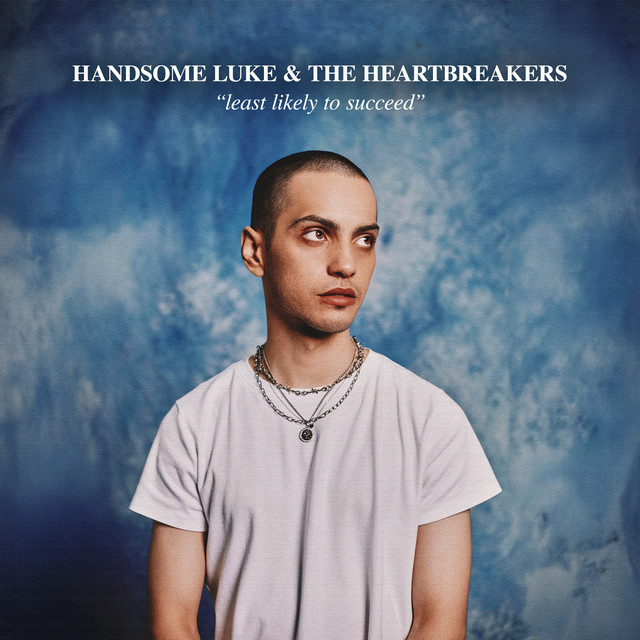

REVIEW: Mars Baby - Handsome Luke & the Heartbreakers

One Year Later: Living With Handsome Luke & The Heartbreakers

A year after its release, Handsome Luke & The Heartbreakers feels less like an album you revisit and more like one you quietly live alongside. Time has a way of revealing what music was really doing beneath the surface. What once felt like atmosphere begins to show intention. What sounded loose starts to feel carefully arranged. And what initially passed as heartbreak reveals itself, slowly, as something more existential.

Handsome Luke is not a character Mars Baby puts on for drama. He reads closer to a developmental self. A version forged in motion, ambition, late nights, and borrowed certainty. Luke is the part of the artist that learned how to survive while becoming something. Charming, restless, sincere, and often misaligned with the people trying to love him. The album does not ask us to judge Luke. It asks us to understand how he came to be.

From the outset, Bleeding establishes the album’s core tension. This is not a heartbreak song so much as a freedom song disguised as romance. Intimacy is framed through movement and escape: crawling down streets, running home, longing for places that were never meant to exist. It is nostalgia without destination. The relationship is a feeling, not a future.

“I’m living for me, but my heart is still bleeding for you.” That line forms the album’s moral fracture. Luke chooses himself but refuses to let go emotionally. Freedom is treated as a value, almost a creed, but it arrives with an immediate cost. Stability slips away. The lyric “freedom makes three” lowkey suggests that liberty, love, and self cannot coexist cleanly. Something will always be left behind.

The religious language matters here too. “If I’m such a sinner then you should save me… Jesus loves me.” Luke absolves himself before accountability appears. He prepares the exit even as he confesses longing. Pain is acknowledged but not corrected. This pattern repeats throughout the record.

That duality, between craving connection and choosing a life that resists it, becomes the album’s emotional engine. Luke moves through relationships like someone perpetually in transit. He longs deeply, but he does not linger easily. In Stay and For You, desire slips into dependence. Love becomes something to negotiate, to bargain for, to bleed through.

“I use these words to keep you here / Dependent on me.” There is nothing romantic about that admission, and the album knows it. This is emotional coercion laid bare. The metaphors surrounding it escalate wildly. Heights, depths, dance floors. Luke is never grounded. He is always above or below himself, intoxicated or unravelling. The chorus sounds like a plea, but it functions more like a confession. He does not ask her to stay because it is healthy. He asks because without her, he cannot function.

Then the heartbreakers enter properly. And everything shifts. The women across this album are not decorative features. They are interruptions. They respond where Luke performs. They ground where he drifts. They reveal what he cannot see about himself in the moment. When lordkez enters Stay, she mirrors Luke’s desperation but reframes it entirely. She removes ego. She names addiction without aestheticising it. Where Luke seeks dependency, she insists on mutual choice. This is the first time Luke’s narration is challenged from within the song itself.

For You pushes Luke’s romantic logic to its most dangerous edge. Here, self-destruction is framed as devotion. “I’ll bleed for you.” and, “I need the pain to be free.” Pain becomes currency. Suffering becomes proof of love. The city imagery is apocalyptic: burning streets, running for cover. This relationship exists only in crisis mode. Calm would kill it. Luke tells her to run but cannot let go. The repeated question “What could I be?” gives the game away. He is using the relationship as an identity scaffold. Without her, he does not know who he is.

A year later, Forgiving You reveals itself as the album’s emotional root system. This is not forgiveness as healing. Sometimes I listen to it and it feels like detachment masquerading as peace. Rehab imagery, amethyst, leaving the body. Luke is dissociating. Forgiveness becomes a coping mechanism.

“Forgiving you was easy / Forgetting all my feelings.” That is not resolution. That is shutdown. And yet, the song complicates itself. Industry anxiety creeps in. Touring. Album pressure. The possibility of failure.

“If no one gives a shit then I’ll go back to college.” Love and career collapse into the same anxiety. Validation becomes currency for worth. And just as Luke seems to harden, the ending betrays him. Repeated texts. “I hope you hit me back.” He has not let go. He has rehearsed letting go.

This emotional logic makes Break Free the album’s ethical centre. Hannah Ray’s verse is grounded, bodily, present. Wind. Breath. Feet on the ground. Freedom here is not escape. It is acceptance. Luke’s verse, by contrast, is still fighting the world. Still screaming into systems. Still measuring worth externally.

And then comes the question that opens the song in a new way with hindsight: “Why’s it so hard to love me?” The line operates on multiple levels at once. It is a question to a lover, to the self, and to the industry itself. Why is it so hard for intimacy to hold him? Why is it so hard for the game to love him back? Why does belief not translate into belonging? Luke is asking into the void, and he is also looking in the mirror. Hannah seeks peace. Luke seeks transcendence. They are no longer aligned. Love fails not from cruelty, but from incompatible ways of surviving.

As the album turns outward, Spotlight and So American peel back the glamour of performance and the entertainment industry. Fame becomes distortion rather than destination. Identity becomes curated, borrowed, hollow.

“When the show is at its end / You’re still performing for no one.” Luke sees through celebrity culture, but he remains trapped in its logic. Anger replaces longing. He draws boundaries but still needs an audience. These songs recall cinematic anti-heroes caught between sincerity and spectacle. Think Robert DeNiro in Taxi Driver, or the drifting creative purgatory of Inside Llewyn Davis. Figures who want to be seen but are unsure what remains when the lights dim.

So American is where the mask slips completely. Sex, money, fame, aesthetics. Love as product. “Half off the love we’re making / in the sweatshop of your affection.” ” America here is not a place. It is a fantasy of excess and vacancy. Luke names exploitation, even as he admits complicity.

Be My Gun pushes this reckoning to its most explicit and unsettling place. The metaphor is ruthless. “I only wanted you to be my gun.” A gun implies protection, power, violence by proxy. Luke wanted someone to fight for him, act for him, carry consequence for him. The heartbreakers refuse this role. They name the cost. Accountability finally appears. Love is no longer romanticised as sacrifice.

And then, finally, Me Too. The album’s quiet epilogue. No drama. Just memory. “Back when our dreams had meaning / Watching our idols on TV, that could be me too.” Youth, dreams, intimacy before ambition hardened everything. "But I'm glad I had the chance to be me with a girl like you." Recognition without blame. Luke does not resolve himself here. He remembers who he was before he needed to be exceptional. It is an ending that feels earned precisely because it resists closure.

One year later, Handsome Luke & The Heartbreakers reads like an emotional journal written in motion. Not a confession. Not a manifesto. But a document of becoming. I don’t think Handsome Luke has disappeared. He probably won’t. But he has been seen clearly now. And sometimes that is the most meaningful kind of growth music can offer. Not answers. Just recognition.