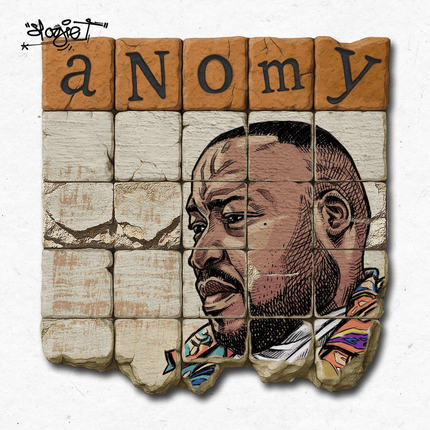

REVIEW: Stogie T - ANOMY

ANOMY doesn’t announce itself as a crisis album. It doesn’t need to. It moves with the calm of someone who has already accepted that the moral centre has shifted, and is more interested in mapping the damage than sounding the alarm. Throughout the album, Stogie T documents life inside collapse without offering false closure, treating success, faith, history, and survival not as answers, but as contested sites where meaning is constantly negotiated, corrupted, and rebuilt.

The album opens in a slaughterhouse.

There’s something unsettling about how calm the song feels while circling ideas of consumption, image, and excess. The "city is an abattoir" metaphor isn’t there to shock. It’s there to frame a worldview. Bodies move through systems designed to process them, polish them, extract from them, and keep them moving. No pause. No ceremony. Just motion.

In Black Venetians, when Stogie raps about surface-level success brushing up against emptiness, “Money make a good servant but a bad master / All is flux, nothing stays still, you adapt or die alone,” it lands less like critique and more like observation.

What stands out to me is how early the album introduces the tension between escape and settlement. Not everyone wants out. Some people just want comfort. Some want access. Some are willing to trade depth for visibility if the lighting is good enough. This is where ANOMY shows up not as a dictionary term, but as a lived condition. A feeling of drift. The sense that the scaffolding holding things together is still standing, but no longer trusted. You can succeed here. You just might not arrive anywhere.

Once access enters the picture, the album turns inward, toward relationships under pressure. Frank Lopez and Hard To Love aren’t interested in villains or heroes. They’re about proximity. About what happens when success changes the temperature of every room you walk into. When silence becomes strategy. When loyalty becomes something you measure instead of assume.

Frank Lopez isn’t just a mob reference. It’s a symbol of false patrons. When Stogie talks about allegiance and leverage, “Frank Lopez, funny style, cockroaches / Sacrifices, stand up guys for such jokers / Pavlovian dogs, devoured the owners,” it captures that shift perfectly. People who offer protection until the invoice arrives. Power that feels intimate until it reminds you who actually controls the terms. The song circles that uneasy space where allegiance and leverage start to blur, where gratitude quietly turns into debt.

Hard To Love takes the same tension and turns it personal. Not sentimental, just honest. Success doesn’t only create distance from struggle. It creates distance from people. From shared language. From old rules. Listening to it, I kept thinking of Bessie Head’s quote in A Question of Power: “I don’t care about people… I want to feel what it is like to live in a free country.” That emotional withdrawal, that fatigue with intimacy, lives in these songs.

I kept circling the same questions while listening: what does loyalty mean when everyone is trying to survive the same scarcity, just at different altitudes? And once access arrives, who quietly becomes expendable?

From there, ANOMY widens its lens. History refuses to stay buried. Colonial brutality, modern warfare, financial abstraction, technological distance. Different tools. Same logic. The album makes it impossible to treat history as past tense. Violence doesn’t disappear. It mutates. Extraction doesn’t stop. It updates its vocabulary.

In Leopold II, when Stogie invokes “15 million children in a tomb,” the line doesn’t land as a statistic. It lands like a ledger. A reminder that generational trauma compounds, that moral debt accrues interest. The distance between king and consequence, drone pilot and target, banker and border is shown for what it is: insulation.

Later, he paints an equally striking image: “Honeymoons in the French Riviera / Told my bride, ‘Mobutu live there’ / Across the shoreline, a stink in the air / The lingering long line of a terror.” It reminds me of Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o’s insistence that colonialism doesn’t just oppress, it normalises the abnormal. When injustice becomes infrastructure, outrage loses its footing. ANOMY shows this without lecturing, placing Leopold, Mobutu, contracts, pipelines, and algorithms on the same moral axis, daring us to deny the continuity.

Sankara’s Grief carries a different tone. Less accusatory. More mournful. It asks what happens to revolutionary possibility after the body is gone but the system remains. When memory survives, but momentum doesn’t. The grief here isn’t just personal. It’s political. It’s about futures that never arrived.

From there, the album moves into emotionally dangerous territory, and it does so carefully.

In Blood Labs, when Stogie describes death as part of the environment, “Where gunshots and sirens harmonize / The good die young, the mothers cry,” it lands because it’s delivered without melodrama. Violence here is ordinary. Death is ambient. Funerals feel procedural, like part of the neighbourhood calendar. A killing draws a crowd the way church bells once did. Sirens harmonise with daily life. Grief doesn’t interrupt. It circulates.

No Healing doubles down on the idea that repetition itself is the problem. Pain loops. Trauma circulates. Communities learn to live around wounds instead of expecting them to close. Despair begins to feel inherited, passed down like a family name. But the album is careful here. It never treats despair as neutral. Someone benefits when suffering becomes normal. When violence feels inevitable. When grief loses its capacity to interrupt the system producing it.

This refusal to romanticise despair echoes something Ayi Kwei Armah once wrote about post-independence disillusionment: that life didn’t change, only the faces in power did. ANOMY sits squarely in that lineage. Clear-eyed. Unseduced by false redemption arcs.

By the time Grande Vita arrives, the album turns its attention to mobility and its myths. Movement without arrival. Wealth without grounding. Visibility without safety. A country where poverty and privilege sit shoulder to shoulder, breathing the same air, dancing to the same beat. The image that lingers is how close everything is: informal settlements in the rearview mirror while gated estates rise ahead like hallucinations.

In Grande Vita, Stogie captures this intimacy with brutal precision, describing “corrugated iron living squeezed into silver,” and later, the “fragrance of the sewer lingering, tainting your couture denims.” It’s not metaphor for effect. It’s documentation.

Win or Lose complicates success even further. What does winning mean when the conditions themselves are unstable? What does it mean when ascent doesn’t guarantee dignity, peace, or permanence? What does it mean to “make it” in a place where success still smells like the sewer? In my opinion, the second verse on this song is arguably the best verse on the album. It is truly masterful work from Stogie T.

The album never mocks ambition. It interrogates it. In doing so, it reminds me of Chinua Achebe’s insistence that the real tragedy isn’t desire itself but losing one’s moral centre while chasing it. Or, as Bessie Head once observed, oppression isn’t only imposed; it’s sometimes internalised and reinforced. ANOMY keeps asking how much of what we chase is survival, and how much is habit.

What ANOMY ultimately offers isn’t resolution. It’s companionship. The feeling that someone else is noticing the same fractures, asking the same uneasy questions, and refusing to lie about how deep they go.

It doesn’t preach. It doesn’t posture. It talks with us, from inside the mess, not above it. And maybe that’s why the album lands the way it does. Not because it explains the moment perfectly, but because it names the condition honestly.

As a society, we're not just broken, we’re disoriented. And ANOMY sounds like someone standing still long enough to notice which way the compass is spinning.

The album doesn’t end with hope or despair. It ends with rubble. And that feels intentional from Stogie T.

There’s no nostalgia here. No longing for a purer past. Reconstruction, as Stogie T frames it, is slow. Unmarketable. Unimpressed with applause. It requires sitting with the damage long enough to understand what failed and why. Witness, not escape.

I don’t walk away from ANOMY feeling resolved. I walk away feeling clearer. More alert. More aware of how easily meaning slips when we stop interrogating the systems shaping our lives.

This isn’t an album offering answers. It’s an album insisting on better questions. And sometimes, in a moment this disoriented, that feels like the most honest place to stand.