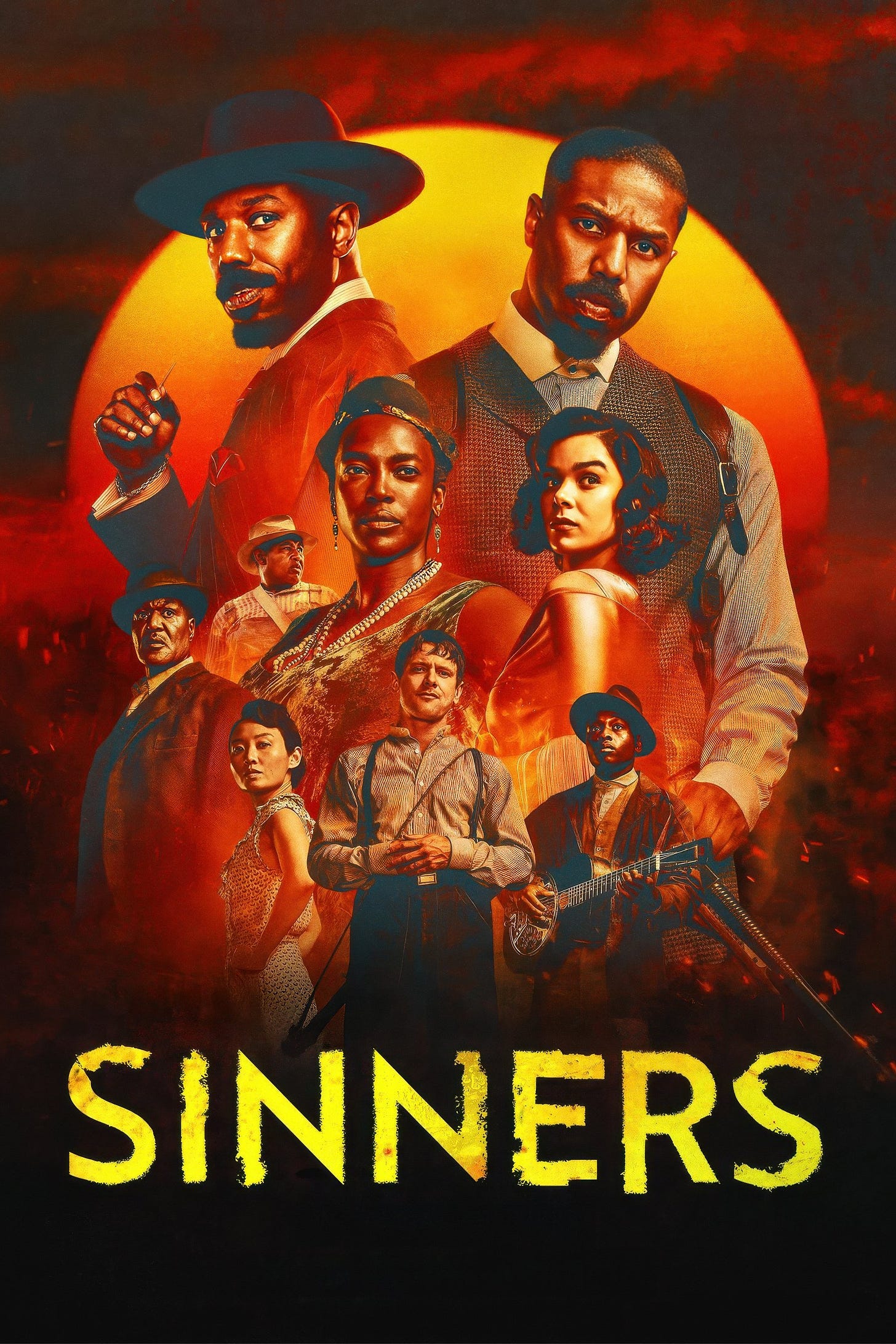

When Music Becomes a Character: How Sinners Speaks Through Song

There’s a special kind of power in films where music doesn’t just accompany; it embodies. Think of Jaws, where those two ominous notes are the shark before you even see it. Or Birdman, where the drums bulldoze through scenes, forcing you to sync with the characters’ pulse. Music can be an invisible lead actor, steering emotion and meaning beneath what’s spoken.

Sinners takes that idea and runs with it. The film doesn’t ask you to notice its music. It asks you to live in it. Before a line is uttered, before a syllable of dialogue, we hear a choir singing “This Little Light of Mine” and later we learn that, for Sammie, that little light was/is his guitar, his voice, and he will do anything to let it shine. From the 1930s Delta of Clarksdale to the present room where you’re watching, music speaks deeper than English. Here, music is not accompaniment. It is the first voice, the truest narrator, and the keeper of centuries that the characters themselves can barely articulate.

That choice is no mere aesthetic flourish. Ryan Coogler has said Sinners is a love letter to his late Uncle James, who spent his nights drinking whiskey, rooting through Delta blues—Charley Patton, Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf—trusting music to keep him company. After his uncle passed in 2015, Coogler kept returning to those records like a musical séance. The movie was born from that memory. Smoke and Stack, the twin juke-joint brothers, are even named after Howlin’ Wolf’s “Smokestack Lightnin’” And in a beautiful circle, Coogler convinced the legendary Buddy Guy to play older Sammie onscreen. The film carries that personal, ancestral heartbeat.

The blues itself grew from work songs, spirituals, and field hollers. It was music that carried grief without breaking under it. These songs encoded escape routes, remembered the dead, and mocked the oppressor under the cover of metaphor. The “devil’s music” label wasn’t about morality; it was fear of the empowerment embedded in the sound. Blues was about keeping a name alive when it had been stripped away. It was telling the truth when the law wouldn’t let you speak it.

In Sinners, these histories converge on the stage. Sammie’s juke joint performance of “I Lied to You” isn’t just a song. It’s ritual. The lyrics are personal, a confession of betrayal, yet the scene erupts into visions: a griot drumming in West Africa, electric guitar screams, a DJ spinning grave-to-present rhythms, dancers from every era. Delta Slim tells him, “Blues wasn’t forced on us like that religion. Nah, son, we brought this with us from home. It’s magic, what we do. It’s sacred… and big.” The scene isn’t musical. It’s mythological, ancestral memory made flesh.

Earlier, in that same juke joint, Mary confronts Stack. Her voice cracks.

Mary: “I know you never planned to stay. Why can’t you just say that!”

Stack: “Say what? That I love you. That I think about you every day. I just wanted to keep you someplace safe. and that was never gon' be here, and that was never gonna be with me.”

That longing, that unspoken affection, you can also feel it in the song, “Mound Bayou” that serves as the score for this specific scene. The blues lay the groundwork, cloaked in longing and resignation. The music speaks for Stacks.

When the Irish vampires arrive, the tonal palette shifts. They enter with “Pick Poor Robin Clean” an upbeat, seemingly playful number originally recorded by Geeshie Wiley in the early 1930’s. In any other context, it could feel innocuous, but here it is camouflage. Their presence is a warning. They are trespassing on Black space, wearing its sound like a costume to lower the guard. The song’s cheerfulness masks threat, the tune an ironic harbinger.

Then comes “Will Ye Go, Lassie, Go?”, a soft, mournful folk love song aimed at Mary when she steps outside the juke joint, heartbroken and unravelling. The vampires know her vulnerability. The melody is gentle and familiar, a siren call not to the crowd, but to her specifically. Emotional seduction as weapon.

Later, “Rocky Road to Dublin” stakes cultural claim. Bright and stomping, the (Irish) vampires use this banger to assert identity and lure others into their influence. It signals “community,” but it’s a hollowed-out, exclusive one: whiteness masquerading as cultural reclaiming. This once-comforting tune now feels predatory, the kind of assimilation that erases difference while claiming unity. Even the instrumentation sharpens the point. It’s played on a banjo, an instrument with roots in West Africa, carried into the Americas by enslaved people before being absorbed into white popular music and Irish-American traditions in the South and Appalachia. The irony is heavy. The very sound that began as Black survival and expression has been obscured, repackaged, and fed back as part of the Irish set-piece.

The rhythm, too, marks difference. The banjo’s strong downbeat drives forward with rigidity, a stark contrast to the swung, lilting phrasing of blues that leans into the in-between. Here, the music isn’t just another layer of atmosphere. It is history colliding in real time, similarity reframed as theft, difference sharpened into tension. This once-comforting tune now feels predatory, the kind of assimilation that erases difference while claiming unity. From this perspective, the melody is both charm and coercion, a musical manifestation of assimilation.

Irish folk and Black blues share histories shaped by colonial violence, but they speak in different tongues. Blues is elastic, improvisational, half-formed in the moment. Irish ballads are tightly structured, story-driven, meant to endure. Both traditions intertwine with religion, hymns, and spirituals. They were tools of solace and also of control. In Sinners, the music converses across these borders. In the juke joint, Sammie’s guitar licks bleed into a fiddle phrase from an Irish folk tune before snapping back to a 12-bar blues progression. They speak without fusing, presence without assimilation, history without erasure.

Songs in both traditions double as confessions. They question divine justice more than affirm it. You could say blues and Irish folk alike drink from religious wells, singing faith, questioning justice, hoping prophecy.

The climactic baptism scene in the third act drives the point home. Remmick dunking Sammie in the river is framed with a Celtic drone chord, evoking religious ritual. It feels sacred, but the act is violent. Christianity twisted into control. Yet Sammie doesn’t stay broken. On the shore, he murmurs the Lord’s Prayer. Redemption rises from his own reclaimed faith.

The score doesn’t just support scenes. It reanimates history in every echo. Theme here, reprise there: what was hopeful becomes menacing. What was restrained becomes liberated. Every note, every lyric is lineage. A blues lick tender in one scene returns jagged later; a mournful fiddle phrase resurfaces as threat. Over the credits, Rod Wave’s “Sinners” anchors the story in the present. Layers of slavery, heartbreak, and survival echo in modern rhyme. Sinners isn’t just a period piece. The music makes clear that these struggles continue.

At its centre, Sinners asserts that music is home. Sammie’s home is those strings, not the preacher’s hand, not the rigid house of his childhood. Mary wants roots. Stack wants safety. Annie wants culture, love, and motherhood. Slim dies for a home worth future generations. Remmick, deprived of home, burns others chasing it, blind to its true meaning. Home is memory, music, belonging.

And so, the line from “Pale, Pale Moon” resonates across centuries:

“From the crow of the rooster / To the mourning dove / Sing my song when the day is done!”

It could be a slave tethered to the fields of Mississippi. It could be an exile on the Irish coast. In Sinners, it is both. And you feel both. Music is the character that carries them, that bridges time, geography, and memory.